Only one species is known to be functionally immortal, and scientists have just compared its genome to that of its mortal counterparts in a quest to find out what makes it so special.

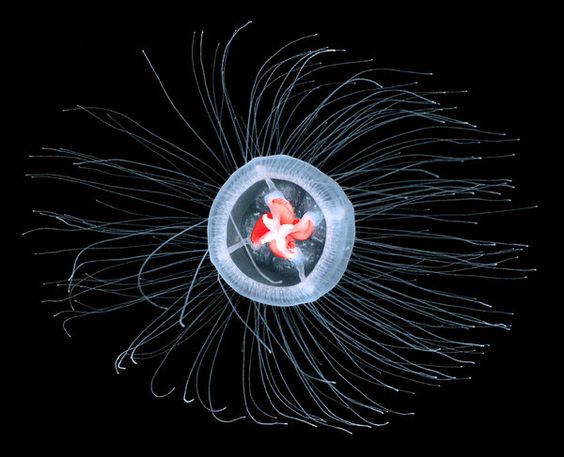

The “immortal jellyfish” returns to a polyp stage after spawning, staying forever young. Then it grows back. Photo: Yiming Chen

Only one species, Turritopsis dohrnii, (which we present here) is known to have found the secret to eternal life. Now, scientists have compared the DNA of T. dornii to its close relative, T. rubra, hoping to shed light on how the aging process works and how we can prevent it.

When T. dohrnii ages, it reverts to its juvenile state. Yeah, like pressing the reset button. Once the adults have reproduced, they do not die unlike other common jellyfish. Instead, they transform back into their juvenile polyp state and the cycle starts all over again, and continues to occur, possibly indefinitely. Known as life cycle reversal (LCR), this happens as many times as the animal wants.

Researchers at the University of Oviedo in Spain have just published research results in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences journal that could explain how T. dohrnii is able to live, at least in theory, forever. To find out, they sampled and sequenced the entire genome of the immortal jellyfish. Once the complete genome was obtained, the same process was carried out with a very close relative of T. dohrnii, Turritopsis rubra, which is not immortal. The team then looked for differences in the genomes that allowed one to live forever and the other to perish.

Juvenile Turritopsis dohrnii jellyfish collected from polyps near Santa Caterina, Nardò, Italy. Credit: María Pascual-Torner

Lead author Dr. Maria Pascual-Torner and co-authors did not discover any genetic trick that could provide eternal life. Nonetheless, they identified a wide range of potential contributors and reported: “We have identified variants and expansions of genes associated with replication, DNA repair, telomere maintenance, the redox environment, stem cell population, and intercellular communication. ”.

The researchers found that in addition to having twice as many genes associated with gene repair and protection as T. rubra, the immortal T. dohrnii also had mutations that allowed cell division to be stunted and prevented telomeres from breaking. Furthermore, the researchers note that during the time that the jellyfish was metamorphosing, some genes related to development reverted to the state in which the jellyfish was just a polyp; this type of life cycle reversal was also not present in the T. rubra genome.

Turritopsis dohrnii polyp from a colony generated by a single rejuvenated jellyfish. Credit: María Pascual-Torner

Applying these findings to humans will not be an easy task, if at all. But while many of the characteristics of T. dorhnii probably only work in combination, some could provide a few precious extra years of health, even for us.

As the article notes: “Natural selection declines with age,” which means that living long, healthy lives after one can no longer reproduce doesn’t have much evolutionary benefit. Consequently, it rarely happens in nature and we only have T. dorhnii to guide us in making it happen ourselves.

However, even T. dohrnii does not live forever. In fact, it has a much shorter lifespan than ours, which is the fate of most small life forms with few defenses that jellyfish and fish find tasty. Thus, although its ability to rejuvenate makes it theoretically capable of living forever, the immortal jellyfish has not yet come to dominate the Earth as one would expect from an immortal species. Lucky for us? Well, who knows…